Access to clean water and sanitation are two fundamental human rights,1 yet billions of people around the world are living without them.2 In 2021, more than 2 billion people lived in water-stressed countries (defined as areas where demand for clean water outpaces supply either because supplies are insufficient or infrastructure is inadequate). In 2022, at least 1.7 billion people used a contaminated drinking water source.3 Relying on dirty, contaminated water leads to outbreaks of several waterborne diseases including cholera, dysentery, and hepatitis A. The World Health Organization estimates that each year some 1 million people die from diarrhea because of unsafe drinking water, sanitation, or hygiene.3

The world has made impressive progress in making safe drinking water more readily available. From 2015 to 2022, some 687 million people gained access to safely managed drinking water.4

Expanding greater access to clean drinking water will require a suite of solutions. Economic freedom can help to deliver meaningful progress by increasing levels of wealth. Governments and private entities will have more resources to expand water infrastructure and households to spend additional resources to hook up water lines to their homes. Competitive and open markets will empower entrepreneurs to develop new methods of water filtration, and strong institutions would provide oversight to ensure that water is being used sustainably and equitably.

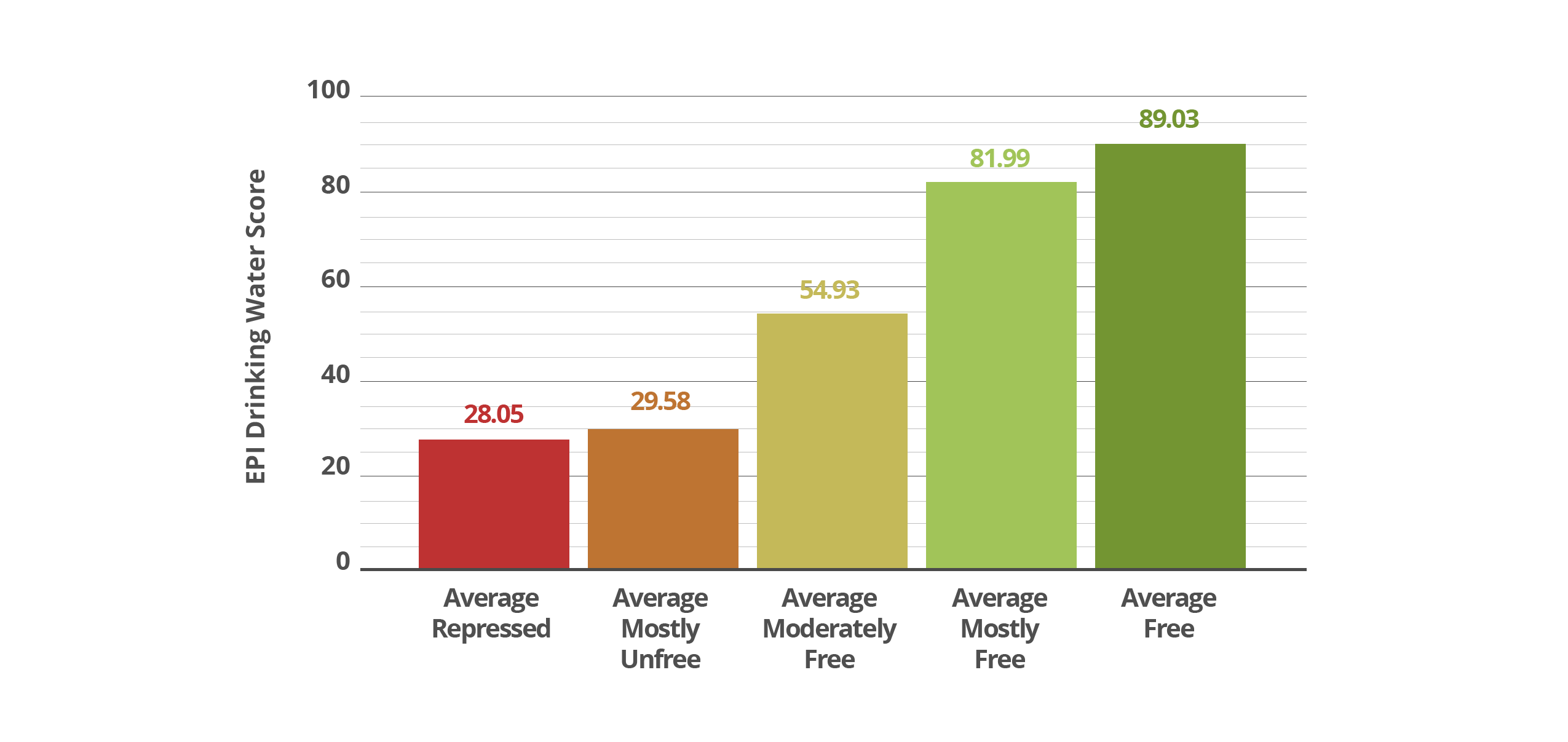

There is a strong, positive correlation (0.669)5 between Heritage’s Index of Economic Freedom and the Environmental Performance Index’s Unsafe Water Index.

Safe Drinking Water and Economic Freedom

Several other studies have identified the relationship between safe drinking water and economic prosperity. One recent and comprehensive analysis comes from Kokou Dangui and Shaofeng Jia in their study, “Water Infrastructure Performance in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Investigation of the Drivers and Impact on Economic Growth.”6 In this report, Dangui and Jia investigate how socioeconomic factors impact water access in Sub-Saharan Africa. The authors also explore the relationship between water infrastructure investment and economic growth.

Dangui and Jai find a “positive statistically significant relationship between water infrastructure, GDP per capita, and population growth, and a negative statistically significant relationship between human capital and regulatory quality.”7 Specifically, the study finds that for every 1% increase in per-capita income growth, water infrastructure increased by 0.2%. As the authors summarize their findings:

The consistent positive association between water infrastructure and per-capita GDP implies that the richer the country is getting, the more successful its water infrastructure performance. This is mainly because countries have more economic resources to invest in water infrastructure and management expertise as they become richer.

In much of the developing world, it is the responsibility of women and children to collect water. Because clean water access can be miles away, water collection takes women and children away from school, education, and other productive activities, all of which are critical to economic growth.8 Improving the levels and accessibility of clean water is not only important for the physical health of citizens, but for the economic and environmental health of countries as well.

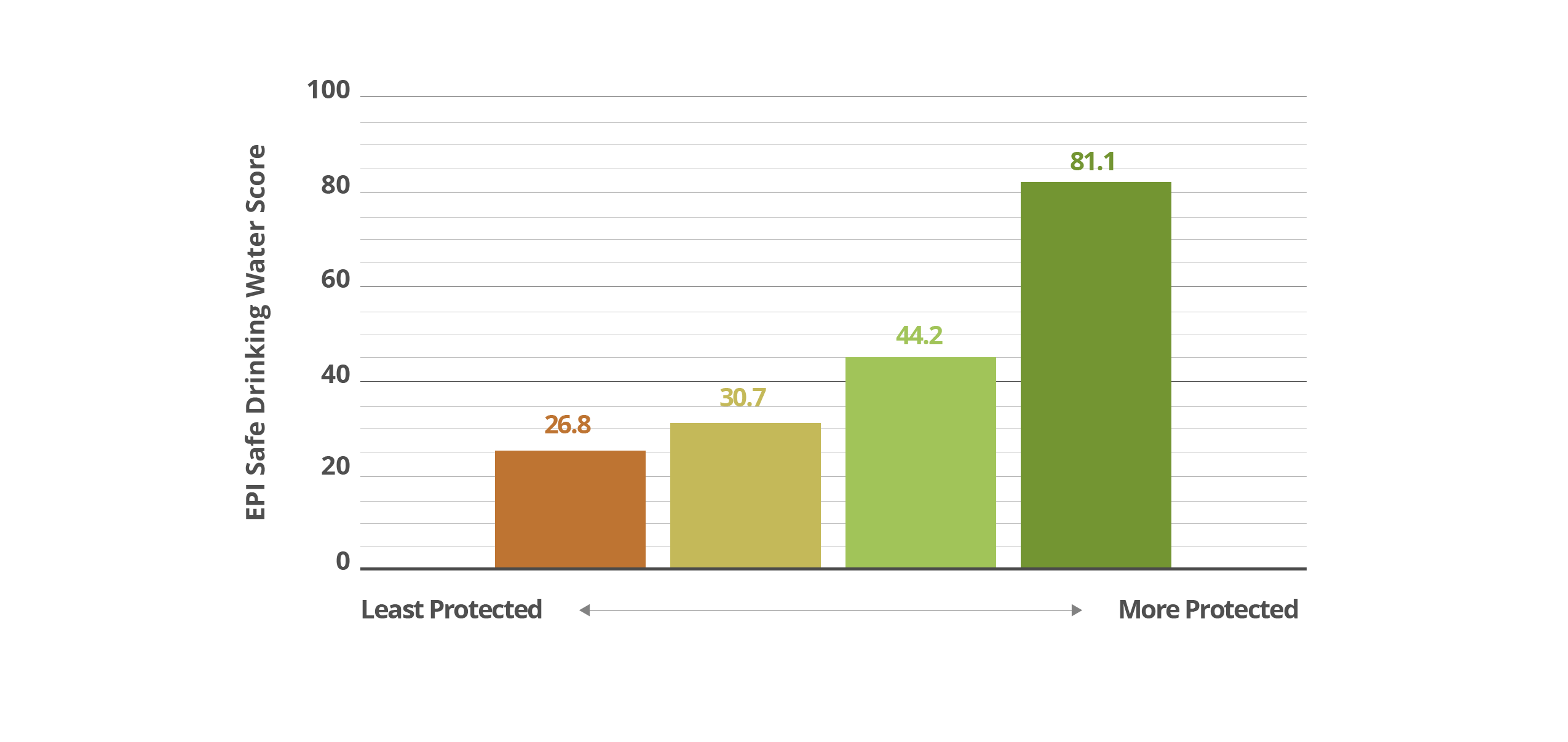

Property Rights and Clean Drinking Water

There is a very strong, positive correlation (0.770) between IEF’s Property Rights subindex and the EPI’s Unsafe Drinking Water measurement.

As seen in the chart above, countries with the greatest property rights protections have safe drinking water scores that are nearly quadruple that of countries with the weakest property rights protections. Expanding water infrastructure is essential to reducing water-borne illness and disease, but unclear roles and inconsistent enforcement of laws can lead to a lack of ownership among governments and communities, stymie investment, and reduce community-level upkeep and buy-in.

A real-world example of the importance of property rights for clean water is Uganda. In an article published in the International Journal of Commons, the authors point to weak property rights protections as one of many factors that prohibit adequate water access in the country.9

Conversely, Switzerland, which has high scores in Yale’s Unsafe Drinking Water subindex and Heritage’s Property Rights subindex, attributes its robust water infrastructure to its strong property rights protections:

Only where the right to own (i.e. sell/buy) is guaranteed, are people willing to invest time and money for the improvement of a common water supply. Thus, the consistent and stable property laws provided a solid framework, not so much for private profit but for common enterprises such as water supply networks.10

The importance of property rights and community ownership is understood not only by the Swiss government, but by the private sector as well. Water4 leverages the power of markets and price signals to expand clean water access in Africa. The company installs water pumps in rural villages and offers training the community to operate, maintain, and fix the pumping technology. Water4 also charges a small fee for the clean water that communities receive which is used to pay for infrastructure upgrades and training programs.11 This not only provides a revenue source, but it also ensures that the community has ownership of the water infrastructure, which incentivizes upkeep and repairs.

Weak property rights protections can also deplete natural resources and lead to water pollution. Because no one oversees and manages the land, no one is incentivized to take care of it, a phenomenon that is often referred to as the tragedy of the commons. Weak property rights encourage resource depletion and weak institutions allow polluters to go unregulated (and potentially violate the rights of other property owners). In Venezuela, which has the lowest possible ranking for property rights protections in the IEF,12 the state-owned oil company PDVSA has freely polluted and drained the land’s natural resources. Despite plans for the federal government to clean up the country’s degradation, at least 200,000 barrels of oil have leaked in recent years, heavily polluting lakes and water resources.13

Similarly, more deforestation occurs with weak property rights and can be detrimental to clean water access. As more land is cleared for agricultural practices, more waste can seep into water supplies and reach consumers. Fewer trees also mean fewer naturally occurring systems to filter out pollutants before they reach water access points. Researchers studying deforestation in Malawi found that “a 1 percentage point increase in the forest ratio increases the probability of access to clean drinking water by 1.06 percentage points.”14

Property Rights Protections and Clean Drinking Water

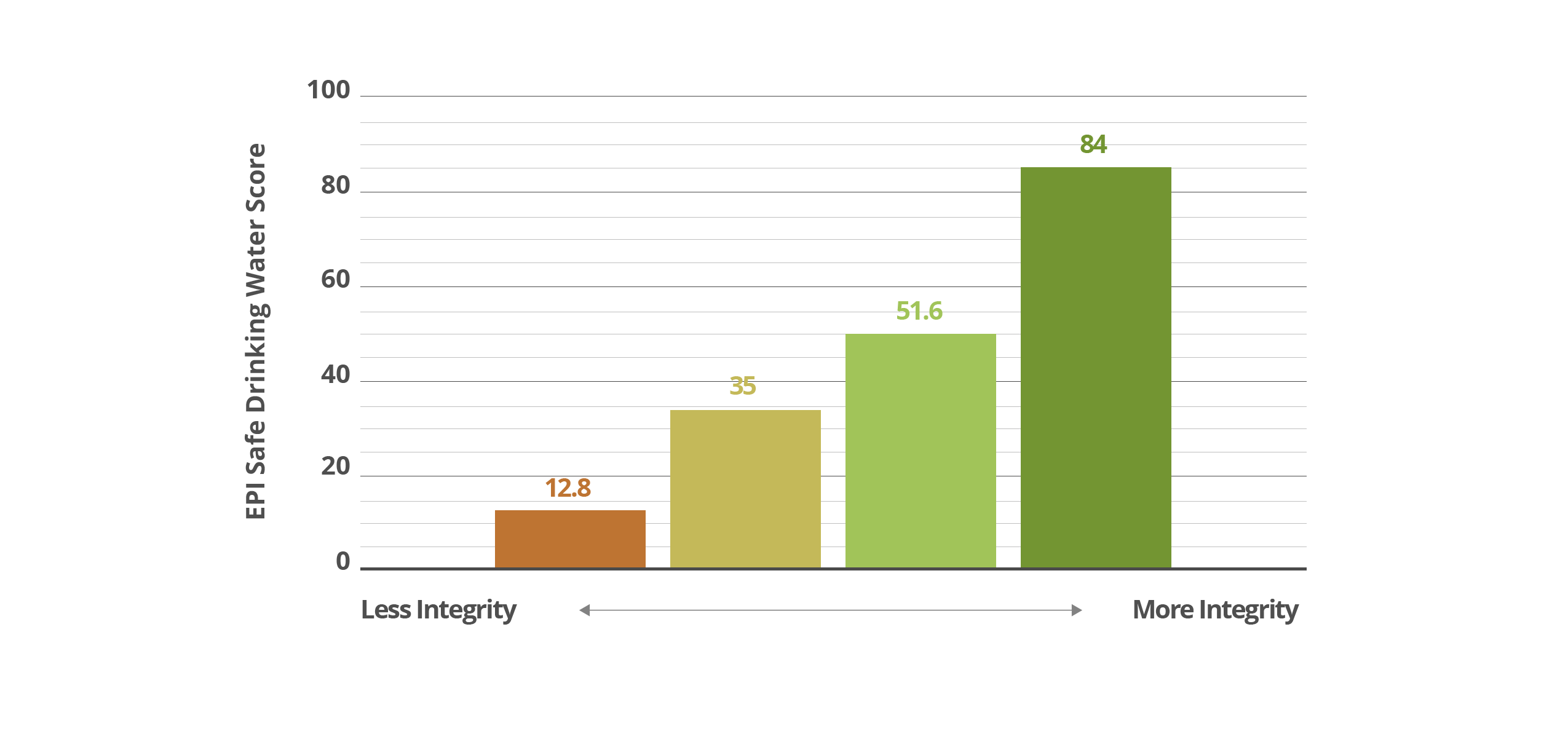

Clean Water and Strong Institutions

For much of the world, water is a public good, and as such its planning and distribution is handled by either the federal, state, or local government. For this reason, government integrity is integral to clean water access. A strong, positive correlation (0.752) exists between Government Integrity and Unsafe Drinking Water.

As countries look to build out key infrastructure to reduce water-related deaths and disease, governments must be able to act effectively and honestly to prevent corruption and the misallocation of resources. Government effectiveness is also essential to the planning of critical water infrastructure especially in population dense, developing countries. Dangui and Jia’s findings support this conclusion:

Further, the consistent negative and significant impact of population density across all income groups supports that the fast increase in the population density is the strongest determinant of water infrastructure underperformance in the [Sub-Saharan Africa] SSA region. Indeed, the impact of population density is lowest in higher-income countries compared to lower-and middle-income groups. These results support the hypothesis that countries with stronger economies may be associated with greater governance effectiveness, allowing for sustainable planning of the increase in population density.15

To decrease the rate of water-borne illness and disease, embracing policies rooted in economic freedom can be a matter of life and death. Specifically, implementing strong protections for property rights and eradicating government corruption will lead to safer and healthier societies.

Government integrity and Clean Drinking Water

- As recognized by the United Nations[↩]

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drinking-water[↩]

- Ibid.[↩][↩]

- UNICEF defines as “Drinking water from an improved source that is accessible on premises, available when needed and free from fecal and priority chemical contamination.” https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drinking-water [↩]

- Yale measures “Unsafe Drinking Water” by: “[T]he number of age-standardized disability-adjusted life-years lost per 100,000 persons (DALY rate) due to exposure to unsafe drinking water. A score of 100 indicates a country has among the lowest DALY rates in the world (≤5th-percentile), while a score of 0 indicates a country is among the highest (≥95th-percentile)[↩]

- Kokou Dangui and Shaofeng Jia, “Water Infrastructure Performance in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Investigation of the Drivers and Impact on Economic Growth,”Water, October 31, 2022, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/14/21/3522[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- OECD (2006), “The Returns to Education: Links between Education, Economic Growth and Social Outcomes”, in Education at a Glance 2006: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2006-11-en.[↩]

- Naiga et al., “Challenging pathways to safe water access in rural Uganda: From supply to demand-driven water governance,” International Journal of the Commons, March 2015, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26522823[↩]

- Matthias Saladin, “Community Water Supply in Switzerland,” Skat Foundation, 2003, https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/community_water_supply_in_switzerland_0.pdf[↩]

- Ericka Andersen, “A Clean Water Organization Brings Life, Hope and Opportunity to Africa,” C3 News Magazine, September 7, 2021, https://c3newsmag.com/a-clean-water-organization-brings-life-hope-and-opportunity-to-africa/[↩]

- “Venezuela,” 2023, https://www.heritage.org/index/country/venezuela[↩]

- Deisy Buitrago, “Focus: Venezuela fails to curb oil leaks, gas flaring despite pledges,” Reuters, August 17, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/venezuela-fails-curb-oil-leaks-gas-flaring-despite-pledges-sources-document-2023-08-17/[↩]

- Annie Mwayi Mapulanga and Hisahiro Naito, “Effect of deforestation on access to clean drinking water,” National Academy of Sciences, April 23, 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26703498[↩]

- Ibid[↩]